| The Missouri Camp Jackson Affair: Forcing Civil Unrest |

| In March of 1861, the same month that the Missouri Constitutional Convention voted 98 to 1 to remain in the Union but not to supply weapons or soldiers to either side if war broke out, radical Unionist Captain Nathaniel Lyon arrived in St. Louis in command of Company D of the 2nd U.S. Infantry. A Connecticut native, West Point graduate and Mexican War veteran, Lyon had been stationed in eastern Kansas during the Kansas/Missouri Border War of the late 1850s, and as a fanatical abolitionist had developed a bitter hatred of pro-slavery Missourians. Gen. William T. Sherman had been a year ahead of Nathaniel Lyon at West Point and described Lyon as a ‘lymphatic boy, who didn’t seem to have energy enough to make a man.’ Lyon was not popular, and he seemed to have developed a mean streak to compensate for his diminutive size. He was once court-martialed for beating a drunken private on the head with the flat side of his sword before tying him up and throwing him in jail, an act for which he was suspended for five months. He went on to be arrested two more times for similar offenses by 1846. This small, unimpressive man often wore a soiled uniform and unpolished boots, but he was an ardent republican who aimed to keep Missouri in the Union by any means, even if it meant ignoring the wishes of the majority of Missourians who were largely in favor of maintaining neutrality in the early days of conflict. Eight days after shots rang out at Fort Sumter, on April 20, 1861, a large munitions depot at Liberty, Missouri was robbed by pro-Confederate forces who seized about 1,000 rifles and muskets. Immediately, the larger St. Louis Arsenal, which contained 60,000 muskets, 90,000 pounds of powder, 1,500,000 ball cartridges, 40 field pieces and machinery for manufacture of arms, became a source of worry to many, including Captain Lyon who had full realization that Missouri Governor Claiborne Jackson, although publicly neutral, favored the South. Jackson had recently rebuffed Lincoln's request for 4,000 Missouri troops to put down the rebellion in response to the attack on Ft. Sumter. Governor Jackson refused to send Missouri State troops, stating it was "illegal, unconstitutional, and revolutionary in its objects, inhuman and diabolical". Jackson wanted U.S. troops out of Missouri and the St. Louis Arsenal, which was under the command of Peter V. Hagner, turned over to State authority to prevent them from being used against "sister southern states". Lyon thought otherwise, and to protect the Arsenal he relied heavily on assistance from the 'Wide Awakes', a shadowy pro-Union paramilitary organization who had previous clashed violently with Governor Jackson and the state Minute Men, a pro-Southern paramilitary organization. Lyon saw to it that the Wide Awakes stockpiled arms and underwent military training in preparation for the outbreak of war. Lyon also sought help from former German revolutionary and now St. Louis school superintendent and unionist Franz Sigel, and together they raised a militia comprised of five nearly all German regiments. Unfortunately, the St. Louis German immigrants were already becoming unpopular with some of the pro-south Missourians because of their strong anti-secessionist political views and strong anti-slavery stance, a position which had been encouraged and influenced by Henry Boernstein, the editor of the St. Louis German language newspaper, "Anzeiger des Westens". Boernstein, in the process of instigating a war mentality among the Germans, also arranged events and lectures by outspoken German abolitionist speakers. Carl Schurz and Lincoln's future cabinet member William H. Seward both spoke to German citizens of St. Louis. (1) Lyon claimed he was aware of a clandestine operation whereby Confederate President Jefferson Davis had shipped captured artillery from the U.S. Arsenal in Baton Rouge to the Missouri State Militia camp in St. Louis, and on May 9, Lyon purportedly went into the camp disguised as a woman, and witnessed the presence of some arms. He took action the following day, using his inspired, but nervous and poorly trained Germans who called themselves the "Die Schwarze Garde" (the Black Guard), to gain control of the arsenal. Upon obtaining command of the arsenal, Lyon armed the Wide Awake units under the cover of night and had most of the excess weapons in the arsenal secretly moved to Illinois. This did not set well with Jackson, who reacted by calling out his Missouri Volunteer Militia for "maneuvers" a few miles away from the St. Louis arsenal in an area unofficially called 'Camp Jackson' which was under the command of Daniel Frost, a Yankee and another former West Point graduate who was appointed as a brigadier general in the Missouri volunteer militia in 1858. Lyon's men forced the State troops to give up, and the 669 man Militia did so peacefully, although 160 men escaped. Not a cheer went up from the German guards. All of the captured men at this muster were not secessionist, in fact, most were, as most Missouri citizens were, in favor of neutrality. Although there were some pro-secessionist flags present, most belonged to members of the more militant Minute Men Militia, a relatively small segment of the Missouri Volunteer Militia. When the soldiers in camp were ordered to take a solemn, but ambiguously worded oath to not only serve the State of Missouri but to protect the "Constitution and laws of the United States", the militiamen refused to take the oath to the Federal government. Lyon took them prisoner and unwisely decided to humiliate them by marching them to the arsenal through downtown St. Louis between two lines of his armed, and surprised, Home Guards. William T. Sherman and Ulysses S. Grant were coincidentally present in St. Louis that day. In addition to the prisoners, Lyon's booty had included weapons smuggled into St. Louis and destined for Camp Jackson, two large howitzers, several mortars, 500 muskets and considerable ammunition. As the men marched through the city on May 10, 1861, depending on the ethnicity and political persuasions of the different areas of town, crowds along the route alternated between jeering and cheering them. In the disorder, some rowdy, drunk bystanders with insults and shouts of "Damn the Dutch" and "Hurrah for Jeff Davis" began throwing fruit, then bricks and paving stones at Lyon's men. Apparently, someone in the mob rushed forward and shot and wounded one of the troops. After Lyon was kicked unconscious by his horse, the frightened and undisciplined troops were temporarily left without a leader. They panicked and fired back at the angry mob. As they began shooting, three militiamen were killed and several civilians wounded. For the next two days, mobs rioted throughout the city and set buildings on fire. Federal troops patrolling the streets killed several people ( either a total of 20 with 50 wounded, 26 with 100 wounded or 28 with 75 wounded, all depending on which account is correct ) before it was over. (2) On the next day, another incident occurred when German Volunteers were fired at and once again return fire into a mob from windows. Rumors were planted throughout the city that the Germans were planning to murder the English speaking population of the city which actually caused some citizens of St. Louis to flee. The Germans were also attacked, however, especially when they were alone and vulnerable, and their families were targeted for abuse from roving thugs. Eventually, martial law was declared and Federal Regulars arrived to relieve the beleaguered German volunteers, but the incident caused incredible and unnecessary bitterness. The Camp Jackson Affair forced most otherwise neutral Missourians to take a side in the conflict. Some former Unionists now even advocated secession, including former Governor Sterling Price. Lyon had accused New York born Damiel Frost of plotting the capture the St. Louis arsenal, and when he denied involvement, Lyon claimed Union intelligence had obtained a letter which revealed Frost's involvement. However, Frost was paroled and then exchanged. Like many others, this event hardened Frost's resolve to join the Confederacy, and he went on to become one of only a handful of Confederate generals born in the North. Most of the surrendered militia men from Camp Jackson had become completely turned against the Federal government but remained loyal to their State and enlisted in the Missouri State Guard which was approved on May 11 by the Missouri General Assembly to resist Union invasion. Its commander was Major General Sterling Price, and on the following day, he and William S. Harney signed the 'Price-Harney Truce' reasserting an earlier agreement to remain in the Union, but as neutrals. On May 30, Harney was relieved of command by Lincoln for failing to deliver Missouri soldiers to the Union cause and Lyon, for his "bravery," was promoted to brigadier general and assigned command of all the Union forces in Missouri. A month after Camp Jackson, on June 11, Lyon and Governor Jackson failed to reach an agreement to deliver Missouri soldiers to the Union cause and Lyon angrily declared war on Jackson´s Missouri State Guard, a move taken despite the fact that in his first inaugural address, Lincoln had assured Southerners that the North would not initiate aggression. The governor and the elected government of Missouri fled, with Lyon in pursuit, to the capitol at Jefferson City. Lyon installed a pro-Union state government in Jackson's place and took chase. Lyon moved up the Missouri River and captured Jefferson City on June 13. Jackson then retreated to Boonville, and on June 17, Lyon defeated a portion of the Missouri State Guard at the Battle of Boonville. The governor, Missouri State Government and the Missouri State Guard then retreated to the southwest under the command of General Price and met with troops under Brig. Gen. Benjamin McCulloch near the end of July. Their combined Confederate forces numbered about 12,000, and they formed plans to attack Springfield where Lyon was encamped with about 6,000 Union soldiers. They marched northeast on July 31. |

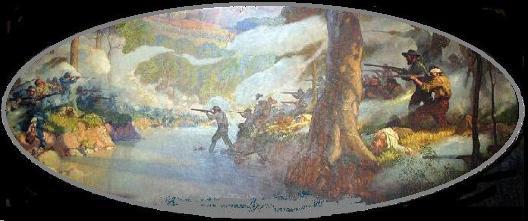

| Lyon and his men moved into position undetected at night and surprised the Confederates on the dawn of August 10 at Wilson's Creek, a few miles south of Springfield . As Lyon was directing his badly outnumbered troops on foot while leading his horse, he was shot in the leg and his horse was killed. Later, he was struck again and grazed on the right side of his head. He staggered to the rear and reformed for a second assault which he decided to lead himself. Borrowing another horse, he led the 2nd Kansas to the fight, but he was hit in the chest, fell from his horse and died. The command was taken over by Major Samuel D. Sturgis, and the Confederates under General Price mounted another assault upon them, but were repulsed for a third time and fell back to regroup, Major Sturgis ordered a fast retreat to Springfield. The exhausted Confederates ordered no pursuit and the battle ended, and it had been much bloodier than expected. In six hours of fighting, the Federals suffered 1,317 killed, wounded and missing and the Confederate/Missourian/Arkansan lost 1,230. News of General Lyon's death and the Battle of Wilson's Creek spread across the country. In October, Governor Claiborne hosted a rump convention that passed out an ordinance of secession. Wilson's Creek gave the Confederates control of southwestern Missouri. Nathaniel Lyon has the distinction of being the first Union general to die in the Civil War. His body was mistakenly (?) left behind on the battlefield at Wilson's Creek where it was discovered by Confederate forces who identified it by the thick red whiskers and "matted hair". Eventually the remains made their way back to Connecticut. Lyon left behind a state torn in two. Governor Jackson did not have to witness the future carnage of the war. In late 1862, Jackson died from cancer at age 56 in Arkansas. 31,000 Germans from Missouri went on to serve in the Union Army. There are no figures for those who fought for the confederacy. Although some historians have called Lyon the "Savior of Missouri", his unprofessional leadership, his inability to compromise with those who wanted neutrality and his poor decisions caused tens of thousands of Missouri men to enter battle and die, cost millions of dollars in property damage and left countless homeless or uprooted families. He and his cohorts took a neutral state and turned it into a state divided. Consequently, Missouri hosted the 3rd most battles in the Civil War. |

| (1) Regarding slavery, Seward alluded to and romanticized the anti-slavery sentiment of Missouri's Germans: "Everywhere I go in Missouri it has been said to me that the Republican Party of this state consists principally of the German population. I am pleased that it is so. For wherever the Germans come, it is their mission to create a way for freedom. Whoever defends right against injustice is in the right place, wherever he might have been born. So let us happily permit Missouri to be Germanized. It was the Germanic spirit that won the Magna Carta in England, it was the German philosophy that has filled the heart of all free men with hope wherever it has penetrated, indeed it was only the German genius that has encouraged freedom throughout the world. So if it is the Germans who are to free Missouri, then let them be Germans. Yet I will not say that one has to be born here or there to have a heart in his bosom glowing for freedom, but I assert that the German spirit is the spirit of tolerance and freedom, and it fights oppression everywhere, whatever mask or disguise it should assume." |

| (2) Nathaniel Lyon's account of the events: Captain C. Blandowski, of Company F. Third Missouri Volunteers, had been ordered with his company to guard the western gateway leading into the camp. The surrendered troops had passed out, and were standing passively between the enclosing lines on the road, when a crowd of disunionists began hostile demonstrations against Company F. At first these demonstrations consisted only of vulgar epithets and the most abusive language; but the crowd, encouraged by the forbearance and the silence of the Federal soldiers, began hurling rocks, brickbats, and other missiles at the faithful company. Notwithstanding several of the company were seriously hurt by these missiles, each man remained in line, which so emboldened the crowd that they discharged pistols at the soldiers, at the same time yelling and daring the latter to fight. Not until one of his men was shot dead, several severely wounded, and himself shot in the leg, did the Captain feel it his duty to retaliate; and as he fell, he commanded his men to fire. The order was obeyed, and the multitude fell back, leaving upon the grass-covered ground some twenty of their number, dead or dying. Some fifteen were instantly killed, and several others died within an hour. Several of Sigel's men were wounded, and two killed. |

| Wilson's Creek |