| Ostpreußen: The Great Trek |

| On April 30, 1732, the very first 843 Salzburgers arrived at their new home but the bulk of them came between May of 1732 and November of 1733. Throughout their trek through Prussia until they poured into East Prussia, pealing church bells and free meals, even for their animals, greeted them in a wave of enthusiasm and moral support everywhere they went. The journey from Salzburg to Königsberg from June 2 until August 22, amounted to 1,500 km. and was covered in just three months at about 20 km per day. 805 people died while on the arduous journey. Those who survived the journey were grateful, humble and well-received. The efficient King set up districts where citizens were appointed to distribute four horses, four oxen, three cows and grain for the first sowing to everyone who had previously possessed a house and land in their former homeland, with all goods temporarily remaining in possession of the State. Whoever farmed satisfactorily could buy them back and purchase more. Devastated East Prussia was renewed with 6 cities and 332 new villages. 180,000 parcels of brushy land were newly cultivated. 3,569 farmhands and farm servants found work as well. The town of Gumbinnen was the center of the East Prussian Salzburger settlement with 15,000 craftsmen and farmers assigned to the town who swore an oath of allegiance to the King. The town had been depopulated by plague and famine before their arrival, and this excited the King's compassion. The oldest part of of Gumbinnen was the market with old highway leading to it, and the old city church was first created around 1545. The basic plan of the city was drawn up by a Königsberger building master and approved on December 18, 1723. In 1739, the hospital the King planned for Gumbinnen was finally established, offering 40 beds. |

| Shortly, part of the former Royal Prussia was merged with the former Duchy of Prussia. The newly annexed lands were to be known as the Province of West Prussia, with former Ducal Prussia and Warmia becoming the Province of East Prussia in 1733, around the time when our story with the Salzburgers begins. The Exiles were offered a home in East Prussia by King Friedrich Wilhelm 1. One cannot separate the story of the Salzburgers from the heart and soul of this contradictory and odd Prussia king with his passionate commitment and his intense personal involvement. Friedrich Wilhelm 1, der Soldatenkönig, came to throne in 1713, and developed an early passion for military life. A frugal man with simple tastes and a bad temper, he took religion very seriously and, although a devout, almost puritanical Protestant, he was extremely tolerant of his Catholic subjects and he detested religious quarrels. His lack of frivolities made him an able administrator, and his policies were upheld for generations after his death. He established village schools, which he visited personally. In 1717, he decreed education compulsory in Prussia. The Soldier King and the Pietists In spite of his harsh reputation, he was much beloved by his subjects and respected for his honesty, practicality and strong sense of charitability and justice. Far from unintelligent, he hoped to build a feared army to act as a deterrent to the other formidable powers. Friedrich Wilhelm's response to his ministers’ recommendation to banish the Catholic religion from Prussia in 1724: "I have a lot of Catholic Lithuanians in the Tilsit lowlands as colonists. If I take away their church services those people will run away. This is a mistake that Louis XIV made (banishing the Huguenots), and I will not copy him. I am populating my land, not depopulating it." Despite his generousity, one dare not mess with the King: He had one Baron Schlubhut hanged for embezzling funds intended for the Salzburgers. From 1722 to 1740, his army grew to 80,000 well disciplined men, gaining him the title of "Soldier King." He was devoted to his army, which suddenly made Prussia the third greatest military power in the world. He "collected" the tallest men from all over to be part of his Potsdam Guards and he enjoyed personally reviewing his troops. He also liked socializing and smoking with friends in his nightly get-togethers called the Tobacco College. |

| Der Soldatenkönig |

| THE SALZBURGERS: EAST PRUSSIA |

| East Prussia was an area which had been devastated with whole villages deserted in the terrible plagues of the Middle Ages and catastrophic famines which followed. Over 30,000 people from the Memel area alone perished and in some areas around Tilsit, not one soul survived. Then, during the Thirty Years War, 13 cities, 249 villages and 37 churches were plundered or destroyed. 23,000 humans were killed and 34,000 had been sent into the slavery. 80,000 more perished as a result of hunger and plague which hit East Prussia again from 1709 to 1711, costing the lives of 240,000 children and 40 per cent of the general population. In 1720, the King of Prussia, eager to repopulate this bleak and barren landscape, published an immigration patent which drew in Swiss Mennonites, settlers from Pfalz, Franconia, Swabia, Nassau, as well as some Dutch, Swiss, Bohemians, French Huguenots and even a group of Scots who settled around Danzig and Elbing. The Historian Lucanus stated in 1748: "In no European landscape was a greater mix of so many foreign nations." |

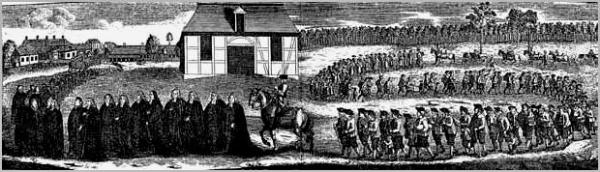

| On February 2, 1732, the King granted permission for the weary Salzburgers to emigrate. His commissioners were sent to arrange care for the exiles' transport and protection. Long lines of refugees left together, many singing Schaitberger's throughout the long, perilous trek from their mountain homes to this distant and alien frontier. Only 6,000 refugees were originally expected, but over 20,000 applied. Their exodus was divided into 32 journeys or treks. The displaced took three routes to Prussia: One way via Frankfurt, a second via Magdeburg, Stendal and Stettin on the Baltic Sea, and the main route which took them through Berlin. From Berlin, they continued to their destination in northern East Prussia in two ways, by land to Königsberg or by water from Stettin. |

10,780 Salzburgers chose the sea, and from there they took 66 vessels in 79 transports.

5,533 exiles chose the land in 11 horse treks with 1,167 horses and 780 loaded carts

| The local aristocrats were reluctant to hire Salzburgers and few families could afford a good home. There was disease, lack of familiar food, a foreign environment and flat landscape. They had to adapt and create a new culture to replace the one which had been destroyed. The king also sent accomplished commissioners to Salzburg to assure the sales of the goods of the emigrants and recovery of their assets, and the Archbishop had been unable to refuse these officials entry. Extra money was used for the Salzburg Institute. The settlers' hard work and diligence paid off. The once depopulated plains blossomed with successful farms and villages. Within a very short time, their unique dialect and old mountain customs vanished as they formed a new culture, the only remaining distinct signs of a Salzburg ancestry being their surnames. Combined with the other immigrants, the total East Prussian population between 1713 and 1740 rose from 400,000 to 600,000 inhabitants. It would be home to the Salzburgers for over 200 years. Of 15,508 Salzburgers who initially settled in the province, nearly 12,000 were first received at the expense of the state and were placed in field, farm or timber cutting work. They received a 3 year tax exemption, generous credits, subsidies to their various construction costs and a release from military service. The King personally developed the highly sophisticated and advanced social program. While the majority of Salzburgers made their new homes in the rural countryside, 715 Salzburgers made a home in the city of Königsberg itself, including 59 woolspinners, 28 woodcutters, 8 shoe- makers, 2 butchers, 53 carpenters, 2 flax binders, 1 coppersmith, 1 draughtsman and a farmhand. The craftsmen enjoyed full freedom of city trade. The new citizens were self sufficient, economical, careful and frugal. Many would become educated and prosperous in the future. Over three thousand Salzburgers found refuge and a new home in Memel, a region sorely devastated by plague before their arrival, and they were greatly welcomed. Memel, near the lower reaches of the Neman River in East Prussia, is a name found in sources from even before the 13th century. Two hundred or so exiled Salzburgers also found a new home in Tilsit and mingled with French, Scottish and Dutch refugees already settled there. Tilsit had grown up around a Teutonic knights' castle known as the Schalauner Haus which was founded in 1288, receiving its city privileges in 1552. It sets on the left bank of the Niemen between Memel and Konigsberg. At this time, Tilsit had a lively trade with ports as far away as Russia. Never very large, Tilsit was a peaceful place with a variety of churches. Other Salzburgers settled in Pomerania and in the East Prussian region called the Masurian Lakes area, comprised of the German rural districts of Osterode, Neidenburg, Ortelsburg, Sensburg, Lyck, Lötzen, Johannisburg and parts of the districts of Angerburg, Rastenburg and Goldap. Some Salzburgers also made their way to Danzig, Elbing and parts of Pomerania. Although most public accounts carefully painted a rosy picture of the new inhabitants, some officials in charge of helping the Salzburgers adjust to their new East Prussian homeland were not so generous, and there are several accounts of mischief and bad behavior among some of the exiles. Sources close to the King complained that they were "excessively stubborn, lazy and pig- headed" and prone to gambling, excessive drinking, promiscuity and chronic complaining. It was said that the young people would often flippantly run off to go looking for old friends. Sometimes described as "discourteous, insolent and coarse, especially when drunk," they were not employed at the estates of the Prussian aristocrats, some of whom viewed the Salzburgers as "hillbillies." |