| Located a few blocks outside of the old Nürnberg city walls, lie two old cemeteries which still maintain much of their original appearance. St. Rochus Friedhof, containing more than seventeen hundred tombs, and St. Johannis, both surrounding the two churches for which they are named, were established around 1395 to bury victims of the plagues. By the fifteenth century, the two cemeteries were largely reserved for the city's more prominent citizens, skilled artisians, musicians, writers ands craftsmen. St. Rochus Friedhof contains more than seventeen hundred tombs, and most of the tombs have their original 16th or early 17th century bronze plaques and about 1000 tomb inscriptions are still preserved. The associated Zwolfbruderstiftung zu Nürnberg, or Twelve Poor Brothers' Charitable Home for Older People, was Joseph's last home. It was founded in the fifteenth century as a brotherhood that catered to elderly craftsmen. 'Das Hausbuch der Mendelschen Zwolfbruderstiftung zu Nürnberg', their housebook, shows many illustrations of the craftsmen and their tools in fifteenth and sixteenth century Nürnberg and is a valuable reference for ancient occupations. The crafts include agriculture, weaving, woodworking, metalworking, leatherworking, candlemaking, barrel making and others. Joseph's new occupation and craft when he went to Nürnberg was the ancient skill of wire drawing. In some cases in antiquity, wire was used to make jewelery by pulling strips cut from metal sheets through holes in stone beads, causing the strips to form thin tubes. This technique was in use in Egypt by the 2nd Dynasty and continued until the middle of the 2nd millennium BC, when most gold wires in jewelery were formed by placing strips between flat surfaces and rolling them into solid wires. This was the strip wire drawing method and a strip and block twist method was still in used in Europe in the 7th century AD. Monk 'Theophilus' in a Westpahlia monestary gave the first European account of wire-drawing around 1100 AD. The greatest improvement in hand wire drawing was the invention of large machines driven by water, thought to have been first invented in Nürnberg by a man named Rudolf. The wire went through two stages: iron bars provided by the smith were made thinner and longer by forging and hammering. These forms were drawn into a thinner form by pulling them through successive steel dies. There was a wire-drawing mill in Nuremberg, Germany in 1370 and a name "Schockenzier" was commonly used to described a wire-drawer. Conrad Mendel refers to business records of wire-drawers from 1366-1500. For the first time a wire factory with a wire-drawing frame was shown. In 1489, Dürer painted a picture of a Nürnberg Drahtziehmühle (wire mill) by the Pegnitz river, pictured below. Joseph worked in such a place. By the 15th century, there were wire flattening mills from Zwickau to Breslau and from Augsburg to Nürnberg. Nürnberg, being an imperial city with the privilege of duty-free trade with over 70 other European cities, was famous for metal working skills such as armor-making and gold-smithing and it had a plethora of talented craftsmen. Jobst Meuler, a wire-drawer in the city around the time of the Thirty Years War, invented a technique for making a steel wire of a far higher tensile strength than anything before. His famous wire was in such demand that in 1621 composer Heinrich Schütz wrote to his patron, the Elector of Saxony, requesting a large order for Meuler's steel music strings. German wire was the finest in the known world at the time. It was even used for strings for guitar and brass lutes of the 15th and 16th centuries. There is a faint image of a wire-pulling machine in the background of Joseph Schaitberger's portrait on his biography page. This was his new occupation when he arrived in Nürnberg. Drawing wire required great strength. Thus, he was laid to rest at St. Rochus Friedhof among many of the finest craftsmen of the world |

| St. Rochus Friedhof |

| JOSEPH SCHAITBERGER |

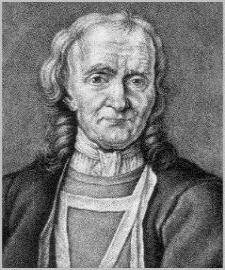

| Above Left: Joseph Schaitberger's grave (782) is at St. Rochus Friedhof in Nürnberg among other historical figures. Famous Nürnberg sculptor Peter Vischer (1455-1529) is buried here along with the great musician Pachelbel and Wolfgang Endter, the printer who first published Schaitberger's book. Right: Joseph Schaitberger as an old man, by Johann Daniel Preisler 1732 |

click